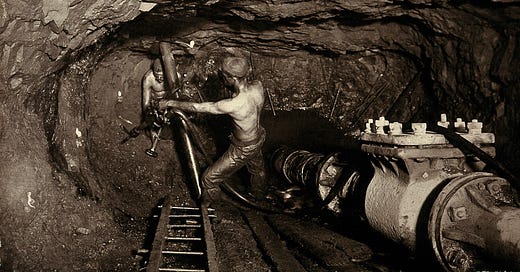

Cornish tin miners, late 19th century. Photo Wellcome Collection.

Apart from my parents, my maternal grandmother Mabel Roach (nèe Pearce) is the only ancestor that I have actually known. * In that sense Granny Roach is not one of the missing pieces of my family story. But my discoveries during this research throws a whole new light on her persona.

My earliest memories have Granny visiting our house in Durban—standing at our front door with a kind smile and a bag of boiled sweets. We looked alike and had the same fuzzy golden hair—which she wore in a long plait wound around her head like earmuffs. When I looked into her face, I saw something there that belonged to me.

Mabel Roach (nèe Pearce), Durban.,circa 1957. Photo Hector Lawson.

I must have been around five years old when it was announced that Granny was coming to live with us. My sister Jane recalled hearing my mother sobbing in the front room and my father saying, “but darling, she is your mother!"

This situation was also greatly relevant to Jane’s well-being. As a young teenager she was now required to give up her bedroom and share mine. Not only did she have to deal with a bratty child rooting through her belongings, but she had to relinquish her beloved dolly varden. For those not in the know, this was a kidney-shaped dressing table customarily dressed in a floral fabric skirt, popular in 1950s South Africa.

Granny lived with us until her death in 1970. During that time, she morphed from a cheerful visitor into a woman whose depressive outlook haunted all the days of our lives. Granny was able to find a cloud in every glimmer of light. I was her pet project, and she was keen to embed her dour Christian values into my repertoire. All I knew of her background was that she was from Lancashire and regarded England as “home”, though she had not visited since her emigration as a child in 1908.

For obvious reasons, when I started working on this project, I was more interested in researching the Roach family. My main goal was to understand how Grandfather Samuel ended up on the gold mines of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. (My interest in that, in a forthcoming post). Not finding a mining connection with the Roaches, I reluctantly embarked on the Pearces.

Perranuthnoe village, 2022. Photo Lesley Lawson

Dismal scenes

It turns out that while my maternal grandfather’s St Ives ancestors were fishing and sailing the high seas, my grandmother’s family were tunnelling the earth nine miles to the south, in the ancient Cornish village of Perranuthnoe. Generations of the Pearce clan had worked the tin and copper mines nearby.

I pick up the trail with Henry Pearce, copper miner, my grandmother’s great-grandfather (Henry 1). He was born in 1799 and married one Jane Cornish from a neighbouring village. Whether they prospered we will never know, but during their 17 years of marriage they produced ten children, eight of whom survived to become miners and domestic workers. Two died in infancy.

When I visited in 2022, Perranuthoe appeared the archetypal idyllic Cornish seaside village with beautiful beaches, quaint cafes and a strong sense of community despite the BnB population. The only obvious evidence of its mining past was the adit, or entrance to mine tunnel, looking for all the world like a cave on the beach.

Adit on Perranuthnoe beach, 2012. Photo Lesley Lawson

But when my ancestors lived there much of the Cornish landscape was disfigured by the violence of the mining process. There were very few trees—since Roman times accessible woods had been cut down to make charcoal to smelt the tin. According to 18th century observers, the typical mining landscape had the appearing of a heap of ruins. One commented that the sand blown from blasting rendered the place “truly dismal, the immense volumes of smoke that roll over it, proceeding from the copper houses, increase its cheerless effect, while the hollow jarring of the distant steam engines remind us of the labours of the Cyclops in the entrails of Mount Etna.”

Another account from 1787 describes the scene outside a Cornish mine: “One stumbles upon ladders that lead into utter darkness, or funnels that exhale warm copperous vapours. All around these openings, the ore is piled up in heaps ready for purchasers. I saw it drawn reeking out of the mine by the help of a machine called a whim put in motion by mules, which in their turn are stimulated by impish children hanging over the poor brutes and flogging them without respite. This dismal scene of whims, suffering mules and hillocks of cinders extends for miles.”

Death and danger

Though improvements in mining technology in the nineteenth century brought some relief, life underground was still dirty, dangerous and rough. Henry 1 died at the age of 50 years—more than likely a result of his job.

In popular mythology the Cornish miner has been romantically viewed as a figure of strength who brought wealth to his family and the country. But the reality was somewhat different. In 1999 a medical historian wrote that in fact the Cornish miner was “part of a sick community whose mortality was amongst the highest in the country, almost entirely because of their occupation.’

A major cause of illness was the poor air quality from drilling and candle smoke in the unventilated tunnels, which caused lung disease. Accidents from gunpowder misfiring also led to loss of hands and blindness. Death from falling rock and drowning were not uncommon.

The Royal Cornwall Gazette of 1846 describes a disaster in a south Cornish mine in which a William Pearce (great-great-uncle?) was one of the 39 dead. A severe thunderstorm of “dense, heavy, purple-black clouds … poured down floods of rain” into the mine shaft, breaking the timber supports and killing the men trapped underground.”

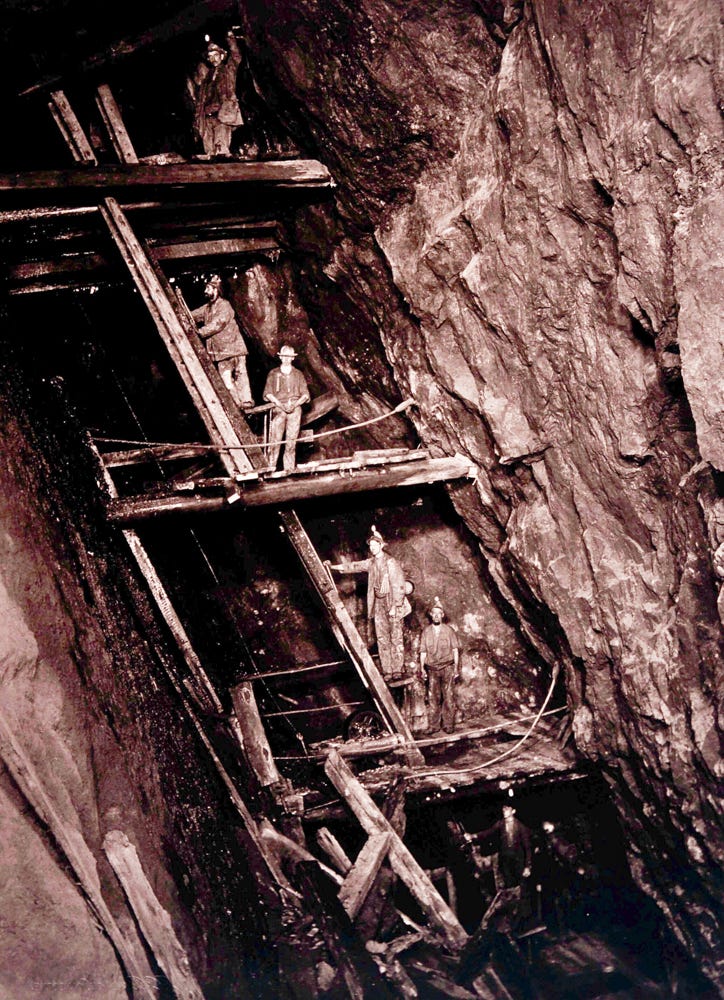

Mines were deep and could only be accessed by up to 600 feet of ladders. Many an accident occurred when climbing up after a long day’s work.

Cornish tin miners, late 19th century. Wellcome Collection.

Daily life

Miners were effectively self-employed, having to quote in advance for anticipated yields and also pay the company up-front for equipment and the candles they needed to light their way. There was money to be made, for sure, but survival depended on a large family team to contribute their wages and cushion the risk.

For most it was a challenge to put food on the table. The typical diet of a mining family consisted of boiled potatoes and salted pilchards. Food was taken down the mine for lunch. At first this was an unleavened loaf, the hoggan, so hard you could drop it down the mine shaft and it did not break until it hit the bottom. Later, miners enjoyed a pie filled with potatoes, turnips and mutton which was kept free of dust and dirt by thick pastry (viz: the Cornish pasty)..

Overcrowded housing, poor water and insanitary conditions were additional risks for poor health and early childhood mortality. Like Jane and Henry’s family, two out of ten babies perished.

Jane’s life was not unusual in that time and place—long childbearing years with the likelihood of being widowed before the children were grown. At the time of Henry’s death, the two youngest Pearces were under four years old, and Jane was pregnant, again. The only solace being that the elder children (including my grandmother's grandfather, Henry2) had gone out to work in their early teens and were at least providing an income for the family. Jane continued to live in Perranuthnoe with her mining sons for the next 20 years.

* I did meet my paternal grandfather a few times, but that, dear reader, is another story.

Thank you for reading. Subscribe for free by clicking the link below. See also my website lesleylawson.co.uk for a version of this post with additional photographs and references.

My father worked as a boiler maker in the copper, lead, zinc, silver mine in my hometown. I imagine the conditions were very different though. I do remember driving in the car with Mum around the huge open cut mine pit to pick Dad up at the end of his shift.

Thank you for the social history. My great grandfather was a miner, first in England, then Nova Scotia, and finally Pennsylvania where he died of injuries sustained in a mine collapse.